Today, more than 1 in 5 pilots in Europe are “atypical” employees, i.e. not directly employed by the airline they fly for. While such atypical forms of aircrew employment had been the exception a decade ago, they have now spread rapidly and widely within all segments of the industry from low cost to legacy carriers.

The repercussions of such precarious employment forms are manifold. They range from lowered social and working conditions for crew, unfair competitive pressures within Europe’s Single Aviation Market, up to potentially negative impact on safety decisions in the cockpit. Many reasons to be concerned – and many reasons to address this, head-on!

According to the University of Ghent study on Atypical Employment in Aviation (2015), more than 1 in 6 pilots in Europe are “atypical” employees, i.e. working through a temporary work agency, as self-employed, or on a zero-hour contract with no minimum pay guaranteed (no flight = no pay).

Young pilots are particularly affected by such precarious employment. 2 out of 5 (almost 40%) of 20-30 year-old pilots report having no direct employment relationship with their airline. Some airlines offer their cadets a position at deplorable conditions, or even resort to ‘Pay-to-Fly’ schemes where the pilot actually pays the airline to fly their aircraft on (revenue-earning) flights.

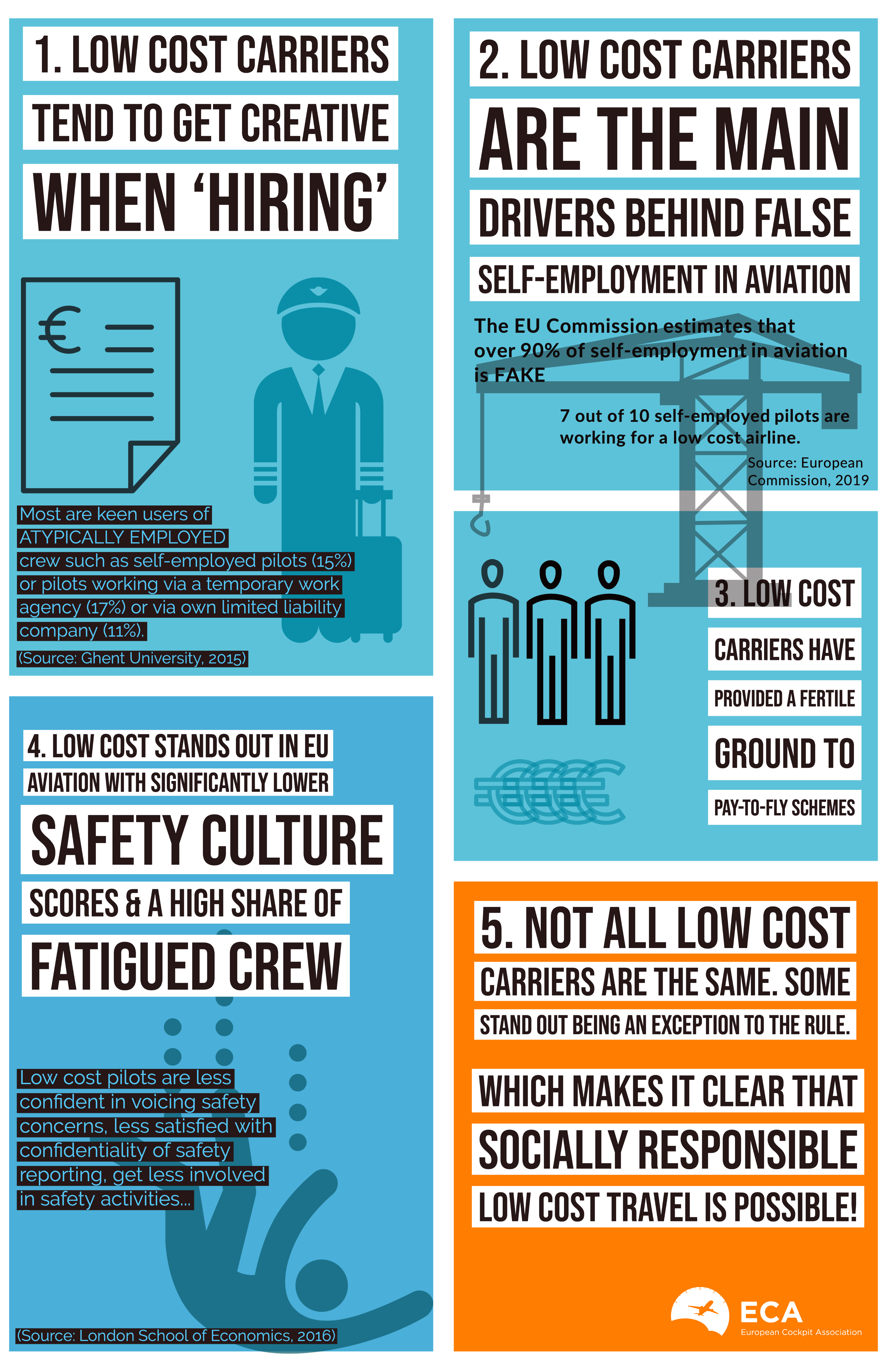

Those pilots working for Low-Cost Carriers (LCCs) are most affected. In fact, LCCs are the largest ‘users’ of atypical employment, in what the Ghent researchers see as a clear divide in the employment market between traditional network carriers and low-cost ones:

• In LCCs only half of the pilots are directly employed (53%), while 15% are self-employed, 11% fly for an airline via an own (e.g. limited liability) company, and 17% are working on a temporary agency contract.

• Self-employment is one of the most prevalent types of atypical employment. 7 out of 10 of all self-employed pilots work for an LCC.

• In network carriers, these “atypical practices” represent a significantly lower share of their workforce: 0.6% of pilots are self-employed pilots, 0.4% fly via an own company and 1.7% work on temporary agency contract, i.e. a total of 2.7%.

So, why are these big proportions and the continuous increase of these “atypical employment” practices throughout the industry so troubling? What can policy-makers, airlines and employees do to stop it?

In 2017-2018, the EU Commission initiated a thorough research into the employment and working conditions of aircrew in Europe. Researchers from the consultancy ‘Ricardo Energy & Environment’ polled around 6000 pilots, 2200 cabin crew, 9 labour inspectorates, 12 employment ministries, 27 airlines, and did targeted interviews & case studies. Not a single broker agency however participated, despite having been invited by the researchers.

Key numbers

1 out of 5 is atypically employed, according to the latest study.

Around 9% of pilots are self-employed. This figure varies among countries, type of air carrier and business model. The majority (88%) are contracted through an intermediary and 75% of all self-employed work for a low-cost carrier.

The self-employment “champions” are Ryanair with almost 60% of its pilots being ‘self-employed’, followed by Wizzair (3.6%). But the researchers are doubting if even a small number of those pilots are genuinely ‘self-employed’.

93% of self-employment in aviation is fake.

The vast majority of self-employed pilots – 90% – are not free to work for more than one airline in parallel, and 93% have no flexibility to decide when or how many hours to fly. Both are major criteria when defining if someone is indeed genuinely self-employed. This effectively means that almost all self-employed pilots are misclassified regular employees.

8% of European pilots are hired or working through a sort of intermediary or a broker. The study suggests that given the high level of complexity of defining if a broker agency is a Temporary Work Agency (in the sense of the EU Directive 2008/104/EC), it is likely that brokers are not compliant with EU and national laws. They do not, or only rarely respect EU Posted Workers rules, they provide bogus self-employed crew to their client airlines or offer consecutive short-term employment contracts to avoid hiring crew on a direct, long-term basis.

Up to 6% of all pilots have been involved in pay-to-fly schemes, whereby young pilots pay the airline for the privilege of gaining flight experience on its aircraft during regular revenue-earning flights. The research shows that pay-to-fly is more common among charter airlines (12%) and low-cost air carriers (8%), compared to 3% of pilots flying for traditional scheduled air carriers.

Posting of workers is also rarely applied in the aviation. While 11% have been posted in another EU Member State, only one fifth of them say the Posting of Workers rules have been applied to them.

The study shows that there is still too much confusion about which labour law applies to air crew. During the study, researchers were faced with airlines still holding on to the wrong practice of applying the labour law of the Principal Place of Business country, instead of the country where the crew have their Home Base. On top of that, few if any labour inspectors and national authorities were aware of the latest very significant and long-awaited European Court of Justice decisions on this subject. The Court concluded that the Home Base is the most relevant factor to determine the aircrew’s applicable labour law (not the nationality of the aircraft registration, or where the Principal Place of Business is located).

This was also a common thread throughout the entire study report: the lack of information and knowledge by labour inspectors, ministries and authorities about the actual labour and employment practices and set-ups in the aviation sector, which is considered as a major stumbling block to addressing the problems adequately.

The liberalisation of Europe’s aviation market and the emergence of new business models – incl. Low Fares Airlines – has given rise to numerous new trends in employment relations for pilots and cabin crew. The study ‘Atypical Employment in Aviation’ (2015) – carried out by Ghent University (Belgium) – assesses the extent of these so-called “atypical” relationships. The study is the result of a survey among 6.633 European pilots and in-depth interviews with stakeholders from 11 countries, incl. air crew, airline representatives and labour inspectors.

Taking self-employment as an example, according to research, this has become one of the most prevalent types of atypical employment (7 out of 10 of all self-employed pilots work for LCCs, according to Ghent University). Yet, ‘self-employment’ among pilots is – overwhelmingly – a status used to disguise what in reality is regular employment. It allows the airline to “shift” social security contribution to the employee, to gain maximum operational flexibility, while minimising its risks – e.g. those related to fixed flight hours, to sickness, pregnancy or fatigue of crews.

For pilots this means that their contracts can be scrapped without notice and flight hours could be withheld. They are paid less or no fixed salary, so they would rely on higher or exclusive use of pay-per-hour, requiring them to fly more hours in order to secure their living. On top of that, there is often uncertainty about which labour law applies to self-employed pilots, which country’s social security rules apply and where to pay taxes. Bringing up a labour dispute or challenging their employment status in Court is also not straightforward as they are unclear about the jurisdiction they are covered by. All this manoeuvring by airlines is to save money and to gain competitive edge vis-à-vis other airlines that do not use such self-employment practices.

This is possible because legislation governing the status of self-employed workers, and labour laws in general, varies from country to country in Europe. Also, only very few countries carry out labour inspections on their airlines, or actively prevent companies from misclassifying the status of an employee. This could easily be addressed if national Civil Aviation Authorities and Labour Inspectorates step up their activities and cooperate both nationally and transnationally. It is positive though that the nature of this (bogus) employment relationship has recently been challenged by a number of tax investigations, as well as by Labour Inspectorates.

The discrepancies between EU Member States – in terms of legislation, oversight and inspections – not only put pressure on airline employees but obstruct a level playing field for airlines in Europe.

In fact, the Single European Aviation Market will only function properly if none of the market players are allowed to achieve an undue competitive advantage by engaging in ‘social engineering’ and employment mal-practices, such as atypical employment. Because if some get away with it and gain market share as a result, the other market players will lose out for playing by the rules. The ones who respect the rules and engage in genuine social dialogue at national and/or company level come under unfair and unsustainable competitive pressure. How long before they also resort to similar mal-practices in order to regain competitiveness?

To maintain healthy and fair competition within Europe’s aviation market, it is therefore necessary to combat this ‘social engineering’ based on atypical employment and to establish direct employment as the norm.

Low cost and cargo airlines stand out in European aviation – with significantly lower safety culture scores and a high number of fatigued pilots in the cockpit – compared e.g. to network airlines. These are among the findings revealed in the largest ever independent study among pilots in Europe, carried out by the London School of Economics and Politics (LSE) and EUROCONTROL (Nov. 2016) within the framework of the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 (Future Sky Safety programme).

The survey among 7.239 pilots reveals that European aviation can pride itself with a generally good safety culture. Using 11 dimensions to define “safety culture”, researchers polled pilots about their perceptions to build a total score for the level of safety culture across European airlines. The results show that pilots are confident in flying, encourage their colleagues to speak up and belief in their colleagues’ commitment to safety.

Casualisation of labour in aviation is more than just about avoiding social security and taxes. It raises potentially serious concerns about the safety of the industry, as the way that pilots are employed (or rather not ‘employed’) can have repercussions on safety decision-making within Europe’s cockpits. When commercial considerations start weighing in the process, the focus on safety is blurred.

According to the Ghent University, nearly half of self-employed pilots struggle to amend instructions of the airline based on their own safety or liability objections! This alarmingly high number means atypical employment can have an influence on the independent decision-making process and safety choices made by crews during or before flight (i.e. balancing the airline’s commercial considerations against the safety considerations).

Similar conclusions were reached by another scientific study among more than 7.000 European pilots. In this study by the London School of Economics (LSE) and EUROCONTROL (Nov. 2016), atypically employed pilots have a significantly more negative perception of their airline’s safety culture than their directly employed colleagues – thereby unveiling a big gap between pilots on atypical and typical contracts. Accordingly, atypical employees are

• less encouraged to voice safety concerns

• feel more obliged to take uncomfortable risks

• are less confident on fair treatment of the safety reporter

• less satisfied with confidentiality of reporting and investigation processes

• less involved in safety activities

• feel more inclined to go to work when sick

• more often tired at work

• less confident to file fatigue reports.

Precarious atypical form of aircrew employment also acts as a significant entry barrier to the profession.

Especially in times of growth, the aviation industry needs significant numbers of new, well qualified pilots to fly the growing number of aircraft. However, on top of the already harsh day-to-day reality of the pilot job, precarious broker agency contracts, artificial ‘self-employment’ set-ups, zero-hour contracts or Pay-to-Fly schemes are definitely not something that will attract young men and women.

Feeding the industry with a sufficient supply of motivated and well qualified pilots therefore relies largely on secure direct employment contracts, governed by the local law of the country where the pilots have their home base. Atypical forms of employment, by contrast, will act as a major deterrent.

More recently, the Swedish Karolinska Institutet study ‘High-flying Risks’ (March 2018) analysed the link between the ‘safety climate’, working conditions and safety behaviours within an organisation. It concluded that worsened working conditions, problematic health & safety behaviours of crews and the prevalence of a ‘high-risk safety climate’ within an airline are closely related.

Atypical employment mal-practices need to be tackled for several reasons:

After years of inaction on the side of the European Commission and most EU Member States, awareness about the downsides of atypical crew employment is growing and calls for concrete solutions are increasing. In October 2018, several EU Member States issued a joint Ministers’ Declaration, calling for a ‘socially responsible connectivity’ in aviation, and several airlines and crew associations, incl. ECA, issued a joint statement on the ‘Social Agenda’ in aviation. Furthermore, the Social Agenda was one of the key items at the EU Aviation Summit, in Vienna, (Oct. 2018), where the need for a strong social pillar of EU aviation was stressed.

To tackle atypical employment, several parallel actions are needed, at EU, national or company level: